- Home

- Michael Shaara

Wainer

Wainer Read online

Produced by Greg Weeks, Mary Meehan and the OnlineDistributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net

Wainer

By MICHAEL SHAARA

Illustrated by ASHMAN

[Transcriber Note: This etext was produced from Galaxy Science FictionApril 1954. Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that theU.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

[Sidenote: _Certainly, life has a meaning--though sometimes it takes alifetime to learn what it is._]

The man in the purple robe was too old to walk or stand. He was wheeledupon a purple bench into the center of a marvelous room, where unhumanbeings whom we shall call "They" had gathered and waited. Because he wassuch an old man, he commanded a great sum of respect, but he was nervousbefore Them and spoke with apology, and sometimes with irritation,because he could not understand what They were thinking and it worriedhim.

Yet there was no one left like this old man. There was no one anywherewho was as old--but that does not matter. Old men are important not forwhat they have learned, but for whom they have known, and this old manhad known Wainer.

Therefore he spoke and told Them what he knew, and more that he did notknow he was telling. And They, who were not men, sat in silence and thedeepest affection, and listened....

* * * * *

William Wainer died and was forgotten (said the old man) much more thana thousand years ago. I have heard it said that people are like waves,rising and riding and crumbling, and if a wave fell once on a shore longago, then it left its mark on the beach and changed the shape of theworld, but is not remembered. That is true, except for the bigger waves.There is nothing remarkable in Wainer's being forgotten then, because hewas not a big wave. In his own time, he was nothing at all--he evenlived off the state--and the magnificent power that was in him and thathe brought to the world was never fully recognized. But the story of hislife is probably the greatest story I have ever heard. He was thebeginning of You. I only wish I had known.

From his earliest days, as I remember, no one ever looked after Wainer.His father had been one of the last of the priests. Just before youngWainer was born in 2430, the government passed one of the great laws,the we-take-no-barriers-into-space edict, and religious missionarieswere banned from the stars. Wainer's father never quite recovered fromthat. He went down to the end of his days believing that the Earth hadgone over to what he called "Anti-Christ." He was a fretful man and hehad no time for the boy.

Young Wainer grew up alone. Like everyone else, he was operated on atthe age of five, and it turned out that he was a Reject. At the time, noone cared. His mother afterward said that she was glad, because Wainer'shead even then was magnificently shaped and it would have been a shameto put a lump on it. Of course, Wainer knew that he could never be adoctor, or a pilot, or a technician of any kind, but he was only fiveyears old and nothing was final to him. Some of the wonderful optimismhe was to carry throughout his youth, and which he was to need so badlyin later years, was already with him as a boy.

And yet You must understand that the world in which Wainer grew up was agood world, a fine world. Up to that time, it was the best world thatever was, and no one doubted that--

(Some of Them had smiled in Their minds. The old man was embarrassed.)

You must try to understand. We all believed in that world; Wainer and Iand everyone believed. But I will explain as best I can and doubtlessYou will understand.

When it was learned, long before Wainer was born, that the electronicbrains could be inserted within the human brain and connected with themain neural paths, there was no one who did not think it was thegreatest discovery of all time. Do You know, can You have any idea, whatthe mind of Man must have been like before the brains? God help them,they lived all their lives without controlling themselves, trapped,showered by an unceasing barrage of words, dreams, totally unrelated,uncontrollable memories. It must have been horrible.

* * * * *

The brains changed all that. They gave Man freedom to think, freedomfrom confusion: they made him logical. There was no longer any need tomemorize, because the brains could absorb any amount of information thatwas inserted into them, either before or after the operation. And thebrains never forgot, and seldom made mistakes, and computed all thingswith an inhuman precision.

A man with a brain--or "clerks," as they were called, after LeClerq--knew everything, literally _everything_, that there was to knowabout his profession. And as new information was learned, it was madeavailable to all men, and punched into the clerks of those who desiredit. Man began to think more clearly than ever before, and thought withmore knowledge behind him, and it seemed for a while that this was agodlike thing.

But in the beginning, of course, it was very hard on the Rejects.

Once in every thousand persons or so would come someone like Wainerwhose brain would not accept the clerk, who would react as if the clerkwere no more than a hat. After a hundred years, our scientists still didnot know why. Many fine minds were ruined with their memory sections cutaway, but then a preliminary test was devised to prove beforehand thatthe clerks would not work and that there was nothing that anyone coulddo to make them work. Year by year the Rejects, as they were called,kept coming, until they were a sizable number. The more fortunate menwith clerks outnumbered the Rejects a thousand to one, and ruled thesociety, and were called "Rashes"--slang for Rationals.

Thus the era of the Rash and Reject.

Now, of course, in those days the Rejects could not hope to compete in atechnical world. They could neither remember nor compute well enough,and the least of all doctors knew more than a Reject ever could, theworst of all chemists knew much more chemistry, and a Reject certainlycould never be a space pilot.

As a result of all this, mnemonics was studied as never before; andRejects were taught memory. When Wainer was fully grown, his mind wasmore ordered and controlled and his memory more exact than any man whohad lived on Earth a hundred years before. But he was still a Reject andthere was not much for him to do.

He began to feel it, I think, when he was about fifteen. He had alwayswanted to go into space, and when he realized at last that it wasimpossible, that even the meanest of jobs aboard ship was beyond him, hewas very deeply depressed. He told me about those days much later, whenit was only a Reject's memory of his youth. I have lived a thousandyears since then, and I have never stopped regretting that they did notlet him go just once when he was young, before those last few days. Itwould have been such a little thing for them to do.

* * * * *

I first met Wainer when he was eighteen years old and had not yet begunto work. We met in one of those music clubs that used to be in New YorkCity, one of the weird, smoky, crowded little halls where Rejects couldgather and breathe their own air away from the--as we calledthem--"lumpheads." I remember young Wainer very clearly. He was atremendous man, larger even than You, with huge arms and eyes, and thatfamous mass of brownish hair. His size set him off from the rest of us,but it never bothered him, and although he was almost painfully awkward,he was never laughed at.

I don't quite know how to describe it, but he was very big--ominous,almost--and he gave off an aura of tremendous strength. He said verylittle, as I remember; he sat with us silently and drank quite a bit,and listened to the music and to us, grinning from time to time with awonderfully pleasant smile. He was very likable.

He was drawn to me, I think, because I was a _successful_ Reject--I wasjust then becoming known as a surgeon. I sincerely believed that heenvied me.

At any rate, he was always ready to talk to me. In the early days I didwhat I could to get him worki

ng, but he never really tried. He had onlythe Arts, You see, and they never really appealed to him.

(There was a rustle of surprise among Them. The old man nodded.)

It is true. He never wanted to be an artist. He had too much need foraction in him, and he did not want to be a lonely man. But because ofthe Rashes, he had no choice.

The Rashes, as You know, had very little talent. I don't know why.Perhaps it was the precision, the methodicity with which they lived, orperhaps--as we proudly claimed--the Rejects were Rejects because theyhad talent. But the result was wonderfully just: the Rejects took overthe Arts and all other fields requiring talent. I myself had good hands;I became a surgeon. Although I never once operated without a Rash by myside, I was a notably successful surgeon.

It was a truly splendid thing. That is why I say it was a good world.The Rash and Reject combined in society and made it whole. And one thingmore was in favor of the Reject: he was less precise, less logical, andtherefore more glamorous than the Rash. Hence Rejects always had

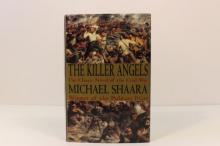

The Killer Angels: The Classic Novel of the Civil War

The Killer Angels: The Classic Novel of the Civil War 2066 Election Day

2066 Election Day For Love of the Game

For Love of the Game The Book

The Book Galaxy

Galaxy Conquest Over Time

Conquest Over Time Potential Enemy

Potential Enemy Soldier Boy

Soldier Boy Wainer

Wainer The Civil War Trilogy: Gods and Generals / the Killer Angels / the Last Full Measure

The Civil War Trilogy: Gods and Generals / the Killer Angels / the Last Full Measure The Killer Angels

The Killer Angels