- Home

- Michael Shaara

For Love of the Game Page 2

For Love of the Game Read online

Page 2

Gus had his mouth open, delighted, figuring. But he had looked at the bed and then was looking at it again and he saw that the bed was crumpled but the pillow was still under the blanket and the bed did not look slept in. Chapel had lain on it during the night but had not undressed. Gus looked round for Carol. No sign. He said: “What … ah … is she here?”

“Nope.”

“Oh, boy. What happened?”

“She didn’t show.”

“Why not?”

“I don’t know.”

“A fight or somethin’?”

“I don’t know.”

“She just … didn’t come last night? Well … didn’t she call?”

“Nope.” Chapel stood up, rubbed his beard. “Need a shave.”

“Well, hell, man, is she okay?”

“Yep. I just called her office. Didn’t talk to her. But … they said she came in.”

“Ah,” Gus said. Then he said, with deep sudden gloom: “Ah, shit.”

Chapel looked down at the pictures near the cassette: that blond girl on skis. He picked up a cassette: Neil Diamond again, put it on automatically, punched the button. He said: “I don’t know anything yet. I don’t understand … not like her. Maybe it’s just … something got in the way. She’ll call later and tell me.”

“Right. Christ, I hope so.” Pause. “You and that woman … well. But what about our plan? Got to hold her to that, the trip to New Zealand—hey, there’s this thing I want to ask you about marriage. Over there. I mean, how about the hotels over there if you check in with the lady who is not married to you? How do they feel about that? I’ve heard there are some places a little … behind the times. Especially them Catholic places. They tell me—hell, you know, I never been overseas—they tell me, a lot of guys, that if you pick up any broad and try to take her back to your room a lot of hotels won’t let her in and I don’t want any of that stuff, certainly not with Bobbie. My God, Bobbie.”

“You shouldn’t have any problem. Not if you check in together. Not that I know of. I never had any. Bringing a girl in, I don’t know about that.…”

Another Diamond song played.

Gus: “But her passport won’t have a married name.”

Chapel: “So if they ask, you got the passport before the marriage, and never did change it. But nobody ever asked us.”

“Good. Great. Takes a load off my mind.” Pause. “Man, have you been to sleep?”

“Forty winks.”

Gus was watching him with concern. “I never been to a real foreign country before. Except parts of Canada. Hee. Hey. They all speak English in New Zealand, right? I mean, do they get sticky with another language, like in Canada?”

“No. They’re kind of … Scotchmen. No problem.”

“Good. The French and me, we don’t see eye to eye.”

Knock on the door. Again open immediately: the tall, lean bellhop whom Chapel had known for years, a cheerful black man named Louie, carrying the usual coffee and rolls and jelly, a broad grin, handsome features in a gleaming face.

“Good mornin’, Mr. Chapel. How you doin’ this mornin’, sir? You got them baseballs all signed? Ah, right. Thank you, sir. Them kids, I tell you, them kids’ll all go through the wall. They all know you, they see you in them commercials. Hey. You pitchin’ today? How about that? You goin’ in there today?”

“Think so.” Chapel searched for the tip. The bellhop was pouring the coffee. Two cups—he’d brought the extra for Gus. He stood up, that enormous grin growing wider. He cocked his arm like a warrior about to hurl a spear. “Well, I hope you blow ’em away. Zoom!” He whirled his arm and fired: strike. “Ha!” He flexed his arm, wrung it out, massaged the muscle with the other hand, like an old and mighty pro. He moved with natural grace—ex-dancer? He was saying: “I live in this town, but that ain’t my team. Motherless bastards. All you gotta do is work for ’em once, and, man, the things I could tell ya.…” He picked up the baseball bucket. “ ’Preciate it, Mr. Chapel, ’preciate it. I know the kids that’ll … well. Good luck, sir. Hope you go out there today and”—he gave a cheery, evil grin—“and dust ’em off, Mr. Chapel. Just dust ’em off.” He departed.

“His own hometown.” Gus was slightly wounded. “Well, I betcha he just doesn’t come from here.”

The Neil Diamond song was beginning to annoy Chapel, and that was unusual: he turned the thing off, stood there, picked up another: old stuff, folk songs, Burl Ives, kept the hands moving, put on another cassette.

Gus: “Got to tell you this, Chappie, I get cold up here in the winter, so, if you don’t mind, I’d just as soon—”

The phone rang.

Carol?

But Gus was near: picked it up.

“Yeah. Right. Who? Well. Okay. Here.” He handed the phone to Chapel. “Manager at the desk.”

Chapel took the thing, put it to the ear. The voice was one of the head men downstairs whose name Chapel did not know. The man was excited.

“Mr. Chapel. Ah, yes. Sorry to disturb you, sir, normally wouldn’t do that kind of thing at all, but, ah, there’s a gentleman down here who wishes to see you, sir, in person, and, well, sir, the gentleman is rather, ah, well, he’s that television personality, sportscaster, whatever the word is, well, everybody knows Ross. I mean, it’s that fella from NBC, D.B. Ross. You’re, well, familiar, of course. If you don’t mind, he, ah, tells me that he must speak to you as soon as possible, that the matter is, ah, urgent, and that he prefers to do it privately, and not on the telephone. Can he come up?”

After a moment Chapel said: “Is he alone?”

“Alone? Oh. Oh, yes, sir.”

“Well. Okay.”

“Fine! Thank you, sir. He’ll be right up.”

News? Something had happened. Clutch in the chest: pressure, warning. No. Don’t think. He drank the coffee.

Gus: “Dooby Ross. Jeez. I wonder.…”

Chapel: “I need a shave.”

Gus: “I’d watch this bird. Chappie, take care. This guy is what they call a ‘showboat.’ Want me to move out? Leave you alone?”

“Hell, no.”

“Shit. This guy, in some ways, is worse than Cosell. Ah. I was hopin’ it was Carol. Hey. Now, Billy?”

“Yep.”

“Want you to know, before somebody comes. I hope you fix that up. I think a lot of her. And if you don’t fix it up—Christ, how long have you known that girl? Years and years. You two … went good together. You looked good together. Matching pair. I mean, with that girl, you laugh. So I really hope—for your sake—Jesus. Is it marriage? Is that the point? Is it time for … time to be practical? Ha? What you think?”

Chapel said nothing. Songs often went through his mind, were singing in the back of the brain while he worked, and that one song was repeating itself there now as he stood by the pictures:

Are you goin’ away, with no word of farewell?

Will there be not a trace left behind?

Well, I could have loved you better

Didn’t mean to be unkind

As you know

That was the last thing on my mind …

Knock on the door. This time it didn’t open. Chapel: here he comes. To Gus he nodded. Gus opened the door: Dooby Ross.

He was famous among television people, had been a sportscaster going back a long ways, back almost to the days of Red Barber, Mel Allen. He was a round, bald man with a flaxen mustache which was his “trademark,” that old-fashioned barber’s mustache. He had a small, round nose, sharp black eyes, a derby he held in his hand. Smartly dressed: a silvery tie, flicker of something diamondlike in the center, a light gray coat. He came into the room, stopped, making an entrance, gazed across the room at Chapel, a brief glance at Gus, then a slight bow.

“Billy Chapel. My pleasure to see you.”

Chapel nodded.

“What’s on your mind?”

The dark eyes were watching, calculating. Chapel knew: he brings bad news. A trade.…

Ross, the showman, pause

d there for a long moment, took a deep breath. Then he said slowly, clearly: “There is some news that will break in a few days. It’s being held back now by the people who know about it, but I found out about it myself last night. I learned from a … friend. Billy, it’s about you.” Pause. “The news shook me up. First thing I thought of was: Billy should know. I owe it to you. After all these years. I owe it to you.”

Chapel, softly: “You don’t owe me anything.”

Ross let that pass. He was making his presentation. He folded his arms behind him. “They made the deal in quiet. Sometime last week. They were going to hold it back until the season was over and not let you know till then. That’s only—a few days off. But they figured it was better not to break the news now. But when they let it loose, Billy, they won’t tell you first. Just as they do so often with … Willie Mays, fellas like that. The big boys they—can’t face. So. You’ll hear it on the news or read it in the paper, and that’s the first they expect you to know.”

Chapel knew: traded. It was a cold blossom blooming in the chest.

Ross: “When I found out about it, last night, first thing I thought was this: he should know. Billy should know. Right now. Let him find it out alone. Don’t let them … mob the guy with questions.”

“Trade,” Chapel said.

Ross, no word necessary, nodded.

Long moment of silence.

Chapel looked at Gus. Gus had turned away. Chapel said, after a while: “Traded. Who to?”

Ross: “Don’t yet know. Not yet. I’m workin’ on it. All I know is, a team out on the West Coast. I got that far. From a girl that … hell. That’s not the point. Here’s the point, Billy. They can get a lot of money out of you right now and they know it, and the word is that you don’t have much more time as a starting pitcher anymore. You’re thirty-seven. They can make big money if they move now. There are a few teams who think that with you in their bullpen they can go to the World Series. And they know how you feel, Billy—” He bared his teeth, gave the look of smelling something sick. “Oh, sure, they know that all right. But dammit, Billy, you played the honorable man all the way. You never came out of the goddam eighteenth century. Christ, Billy, you never made any real legal deal. They’ve got you by the balls, by the living balls, and they know that, I know that, goddammit, you know that. You must know that. You just never thought—while the Old Man was around. But Billy, he’s gone now. And the little men are in there now. And, Billy Boy, you’re gone now, too. That’s the goddam miserable shiteating truth. You won’t be with the Hawks next year. Billy, it’s done. And there’s nothin’ you can do.”

Chapel turned, saw a chair; sat.

Music from the cassette: “The pony run he jump he pitch … he threw my master in the ditch.…”

Chapel cut it.

Stillness.

Empty inside. Nothing there. Head gone empty.

Song was: “The Blue Tail Fly.”

He heard Gus swear. Chapel looked up vacantly, smiled, seeing nothing. Remembered the Old Man, smoking a big fat brown smoky cigar: “Billy, goddammit, one of these days, goddammit, you got to grow up and play for money, like they all do. All them little bastards.”

Chapel nodded. But … I never did.

And now … seventeen years with one team. Signed … on the front porch with the Old Man and Pop all those years ago … vision blurred. Ah, but the Old Man loved the game, and Pop loved the game, and I loved it so … and every year, the Old Man did the best he could … in the office, the round, frowning face: “Billy, kid, this is the best I can do. But you are the best no matter what I do. But I can’t do better. But if this bothers you, Billy, if it ain’t enough, you tell me, and I’ll try, so help me, I’ll borrow someplace. Billy, what do you want?”

The Old Man is gone.

What do you want?

Knew this day would come.

Did you?

Yep. But. Well.

It’s come.

Yep.

Chapel had seen this coming, knew it was coming, and had planned nothing, nothing at all.

Ross was watching. No questions. He turned to Gus, eyed, calculated.

“You Gus Osinski, right? The catcher?”

“Yep.”

“You’re hitting, ah.” Ross put a finger to his nose, a famous position of mind packed with filed numbers. “You’re hitting right now … 206. Am I right?”

Gus grunted. “Close enough.”

Ross smiled, blinked, his mind moving along, rounding bends, from Gus to Billy and back. Ross said: “You know the point, Gus. They’ll say to the home fans he’s over the hill. Look at the record this last year.…”

“Look at the club behind him. Look at that batting average. That bunch can’t hit as good as me.”

“I know. But the records, the numbers … and his name. Seventeen years with the same club. The novelty of it. To have Billy Chapel on the mound for … them, whoever the hell they are, maybe LA, maybe the Giants. They’ll pack ’em in out there for a while, just to see him, root for him. Even if only a few innings at a time.… Even if only in relief.…”

“Billy? In relief? Ha. Not him. Never. Never.”

“He won’t go. You don’t think so.” Ross turned back to Chapel. Billy sat there, no expression at all, drinking coffee. Ross came forward, stood in front of him. His speech was faster now, more intense: he was getting to the point.

“Billy, I came here because I thought I owed it to you. Now, I do”—he put out both hands—“I know that in ways you never will. So. I thought I could let you know this thing in private, away from the crowd, the way they’ve done it so often. I didn’t want to see you, Billy, with them asking all those questions in public. So.” Pause. “I came up as fast as I could.” Pause. “And now you know the facts. You know what they want to do. But, Billy … I have a hunch.” He cocked a finger, like a man about to pull the trigger on an invisible gun. He smiled a strange, soft smile. “Billy Boy, Chappie, you’re the best I ever saw. I don’t say this for publicity. No cameras watching. But I want you to know what I think. After seventeen years … Billy, you’re the best.” Pause. He had said something that to him was very important and very unusual. Then his face recovered, and there came back that crafty natural grin. “So. You are the best. And when a man like you is truly the best and knows it, like Ted Williams knew it, and DiMaggio, and a few of the golden boys, there comes that special pride.” Pause. Smile. “I think I’ve got you figured, Billy, but … who knows? Still … I’ve got this guess. You have been traded to another team after seventeen years with the Hawks … one place, one home, and now they’ve let you go; no, they’ve thrown you away. They do that to all the big boys sooner or later. Hell, they did it to Babe Ruth, to make money, and he went, and Willie Mays, and Maury Wills. And most of them … they go on playing. But, Billy”—he leaned forward now, face coming in closer to Billy’s face, eyes there boring into Billy’s eyes—“with you, Billy, I think it could be different. Some of the guys didn’t go. There were guys like Williams, and Joltin’ Joe. They had the pride. When they were done, they were done. Isn’t that so? You know it like I do, yes you do, Billy, you know the pride. When they were done, when there was the first flaw, when the leg didn’t quite work anymore for Joe or Williams wasn’t exactly the best anymore, as soon as the hints were there, even the hints, they would play no more. They were done. They would take no trade. Willie Mays … Willie, I saw him out there one day, drop a fly ball. Tears in his eyes. But he had to go on. Some guys love it that way, the pride doesn’t matter. Some guys, just the money. But you, Billy … well. Will you tell me? Are you done? Or will you go on to another team? What’ll it be?”

Chapel sat for a long moment in a silent room without any motion. Ross couldn’t wait. He said: “I came to you with the news, to break it to you as a favor.”

Chapel nodded, said nothing.

“Now, Billy, will you do this for me, will you tell me what you’re going to do? Can you tell me now? Because B

illy, now that you know, I’ll tell you this: I’ve got a hunch. A big hunch. It will make big good news. Billy, I don’t think you’ll go. I think you’re done.” Pause. Silence. “Am I right?”

Chapel didn’t want to sit anymore, didn’t want to talk. He stood up rubbing his face. He said: “Shave, I think. Excuse me.”

He walked away. Ross said nothing. Chapel went into the bathroom and closed the door. He felt pain and darkness for the first time. Hit very hard. He went mechanically to the mirror and looked into it and did not see himself as he began to soap his face. He thought no words. For a moment he saw the happy face of his father, Pops, pounding a hand in the catcher’s mitt they had practiced with when Billy was a pup, and he heard Pop’s voice: “Come on, Billy! Throw hard now, Billy Boy!” He began slowly to shave. Softly, the old folk song: “Oh where have you been, Billy Boy, Billy Boy? Oh where have you been, charming Billy?”

First thought: I guess he’s right.

Chapel stopped shaving.

Time to go home.

Play no more?

At all, at all?

“What, never? Thou’ll come no more, never?”

This … is a hell of a day.

He tried to clear the mind but it wouldn’t clear, wouldn’t think. He finished shaving, stood there by the door, not wanting to go back in to talk to Ross. One more moment. He heard Ross’s voice:

“… for four years with that man, right? Yes, I know, you’ve been traded yourself, what, three times? Not the same thing for you, is it? But him? Listen, you’ve been catching Chapel for four years. You know him like nobody else. What do you think? Go ahead, give it straight. You think he’s over the hill?”

Gus’s voice, sudden and harsh:

“Horseshit! Ole Chappie? Over the hill? Pure horseshit! Listen, ace, you try and catch him yourself, first few innings. Hail Mary. Give him to anybody. Then stand back. He is … he is still the fastest I ever saw, and along with that the control. My God, near perfect. He does it all. Shit, he can thread needles with bullets. With any kind of team at all … hell, he still holds half the records. Christ, you know that. And he’s thirty-seven. So what? Only problem is he … he just doesn’t last as long as he used to. He tires earlier. A little like Ole Bobby Feller. He wasn’t before your time, you remember him. Christ, if baseball was a game only lasted six innings nobody ever would have beaten that guy. But he tired … a little too soon. And Billy’s now that way. In the beginning, nobody hits him. Those first few innings, God Almighty … he was always the best. He’s still the best. Hell. Ask anybody. Anybody who has to go up against him.”

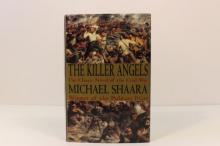

The Killer Angels: The Classic Novel of the Civil War

The Killer Angels: The Classic Novel of the Civil War 2066 Election Day

2066 Election Day For Love of the Game

For Love of the Game The Book

The Book Galaxy

Galaxy Conquest Over Time

Conquest Over Time Potential Enemy

Potential Enemy Soldier Boy

Soldier Boy Wainer

Wainer The Civil War Trilogy: Gods and Generals / the Killer Angels / the Last Full Measure

The Civil War Trilogy: Gods and Generals / the Killer Angels / the Last Full Measure The Killer Angels

The Killer Angels